This primer is available as a white paper, and can be cited as "Estes, S. (2021). Cogulator: A Primer [White paper]. The MITRE Corporation. http://cogulator.io/resources/primer.pdf"

Preface

Cogulator is a simple human performance modeling tool for estimating task times, working memory load, and mental workload. It's designed to be approachable for new users and quick for experienced ones. In short, we have tried to create a tightly focused application for building GOMS models by applying basic human factors to a basic human factors tool. If you're not familiar with human performance models generally, or GOMS specifically, the magic models feature is probably a good place to start (video), as it'll automatically build models for you.

Design

There are a number of GOMS software tools available today. Those include efforts like GLEAN (a significant influence on Cogulator) which provides a quasi-programming language for developing models that can be embedded in real- and fast-time simulations. Other applications – CogTool being a primary example – forgo programming in favor of graphical approaches to constructing models. Cogulator is not meant, necessarily, to compete with or replace any one of these and, depending on your goals, any one of these may be a better choice for you. What sort of goals would suggest the use of Cogulator? Building models quickly and flexibly OR a need for estimates of mental workload.

In most modeling systems adding new operators or changing default operator times requires changes to the codebase. We found that to be a major obstacle in modeling. Any time we learned something new about a domain - say, the rate at which air traffic controllers speak when issuing clearances - the proverbial hood on the modeling tool's codebase had to be opened. Cogulator, therefore, allows the user to quickly and easily add new operators; permanently change the execution time of existing operators based on domain knowledge, empirical evidence, or simple curiosity; or make a change to the execution time of a specific occurrence of an operator - all without touching the application source code.

One of the side effects, or perhaps requirements, of allowing operator flexibility is a corresponding flexibility in the modeling language. As it happens, this also matched up well with our needs. For some projects a Keystroke Level Model (KLM) model was adequate where others required a detailed, CPM-GOMS (Cognitive, Perceptual, Motor) or, at an even lower level, Human Information Processor (HIP) model. Instead of focusing on a particular iteration of GOMS, Cogulator allows for building across a wide range of GOMS implementations including: KLM, NGOMSL (Natural GOMS Language), CPM-GOMS, CMN-GOMS (Card, Moran, & Newell), or HIP. While this flexibility has obvious advantages, it also leaves it to the modeler to determine what operators are appropriate for a particular model.

Aside from flexibility, Cogulator was built for speed. In general, there’s a design tradeoff to be made between the approachability of a GUI based interface and the speed of a text-based interface. In the case of Cogulator, experience with other GUI-based modeling tools as well as recursive GOMS models of building GOMS models, as it were, indicated that there is just no faster way to build models than via a text-based interface. And, we found that with a flexible syntax, we could retain much of the approachability of a GUI.

Syntax

For Cogulator we wanted a syntax that was linear and easily readable - even to someone unfamiliar with it. At its simplest, that means something KLM-like. So, in Cogulator it's perfectly acceptable to simply enter a series of operators to get a task time. For example, pointing to a target on screen with a mouse requires the user to first look where they want to point, move the cursor with the mouse until it is over the target, and often verify mentally that the cursor is in position. In Cogulator, a perfectly valid model of this task is built with just three words:

Look

Point

Verify

Sometimes you'll want something a bit more detailed. For that, we just add goal statements and hierarchy via CMN-GOMS.

CMN-GOMS

CMN-GOMS was first introduced in Card, Moran, & Newell’s 1983 book, the Psychology of Human Computer Interaction. Our implementation is a mash-up with a KLM approach to operator definition and bears a very close resemblance to NGOMSL, as developed by David Kieras. CMN-GOMS is a hierarchical syntax (and, in fact, the original formulation of GOMS). This is a nice fit with task analysis as the model is essentially a step-by-step guide for completing some task (and avoids some conventions that may be foreign to non-programmers like functions or procedures). Returning to the previous example, we can add a goal statement and indents to indicate hierarchy, creating a CMN-GOMS version of the model:

Goal: Point Click

. Look at target

. Point to target

. Verify cursor over target

To create a CMN-GOMS model we've added a goal statement that describes the task being completed and some periods to convey hierarchy. Each operator required to accomplish the goal is preceded by a one period more than that of its goal (in this case, the goal had none, so each operator is preceded by one period). Essentially, CMN-GOMS allows you to create an outline of the task. The periods are important because they indicate to Cogulator where goals and operators lie within the hierarchy of the model. As a final example, if we wanted to add a subgoal to the Point and Click goal, it would have a single indent:

Goal: Point Click

. Look at target

. Point to target

. Verify cursor over target

. Goal: Subgoal Point Click

Operators

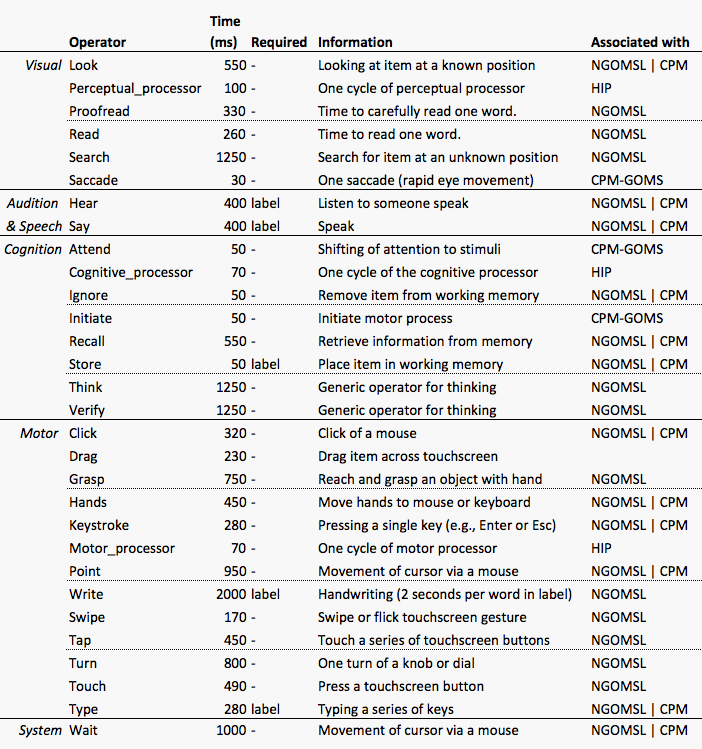

Cogulator comes with twenty-nine operators pre-installed, to which you can add more. Operators have three components: the operator name, an operator label, an operator modifier. The name is the operator itself (e.g., Point for pointing a mouse or Look for looking at something on the screen). The label, which describes how the operator is being used, is typically optional (Type, Listen, and Say require a label in order to determine how long the step should take). So, if I wanted to indicate that a save button is what is being pointed to in a model, I could enter:

. Point to Save Button

You can enter anything you want for the label and it can be as long or short as you would like.

Each operator has a built-in task time. Point, for example, has a default time of 950 milliseconds. If you have a need to use something other than the default operator time, the execution time of the given instance can be changed by using a modifier. Modifiers are contained in parentheticals added to the end of the line:

. Point to Save Button (300 ms)

where ms stands for milliseconds. You can also use "seconds" or, for audition and speech, "syllables". A full list of operators, their definitions, and required parameters are shown in the table below.

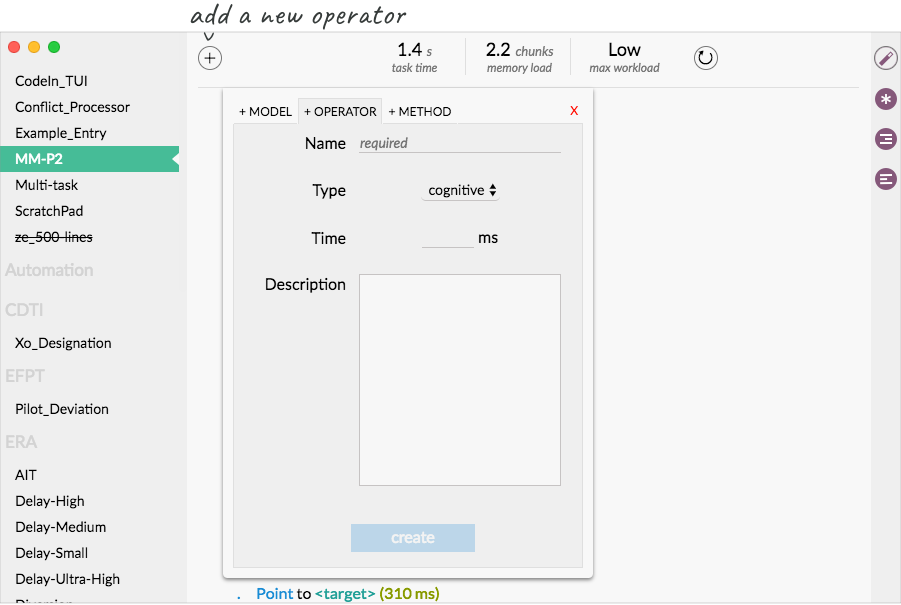

If you find you need an operator not included in Cogulator, you can add one by clicking on the new button and selecting the Operators tab. The interface that pops up will require a name (no spaces), an operator type (is this something you do with your hands, speech, audition, or with cognition?), and an operator time in milliseconds. You can include a description if you'd like. Once you've got all the information entered, just press your Enter button to add the operator to the list. You can start using your new operator immediately.

There a few operator options not exposed by the new operator interface. To get to those, you'll need to add the operator manually to the operators.txt file in the Documents folder of your computer. Windows users will find the operators.txt file by going to:

C:\Users\Documents\cogulator

and opening the operators folder within the Cogulator directory. OS X users can find the cogulator directory in their Documents folder. When adding a new operator to the file, include the resource (see, hear, cognitive, hands, or speech), followed by a space, the operator name (no spaces in the name), another space, and the execution time in milliseconds. For example, if I wanted to add a new operator for touching a target on a touch screen device I could add the following line to the operators.txt file:

hands Touch 250

In the operator file you can also optionally provide an operator description and, starting with v1.3, a tag to tell Cogulator to use the words in the label to determine step time. The description should have no spaces in it (use underscores between each word). The optional tag can be either "count_label_words" or "count_label_characters". The first will count the total number of words in the label and mulitply that number by the supplied operator time to get the total time for the step. The princple is the same for "count_label_characters", but the number of characters in the label are used as the multiplier. Here's an example of a new operator with a description and label tag:

see Read 260 Read_a_single_word. count_label_words

Once done, save the operators file and relaunch Cogulator.

Interface

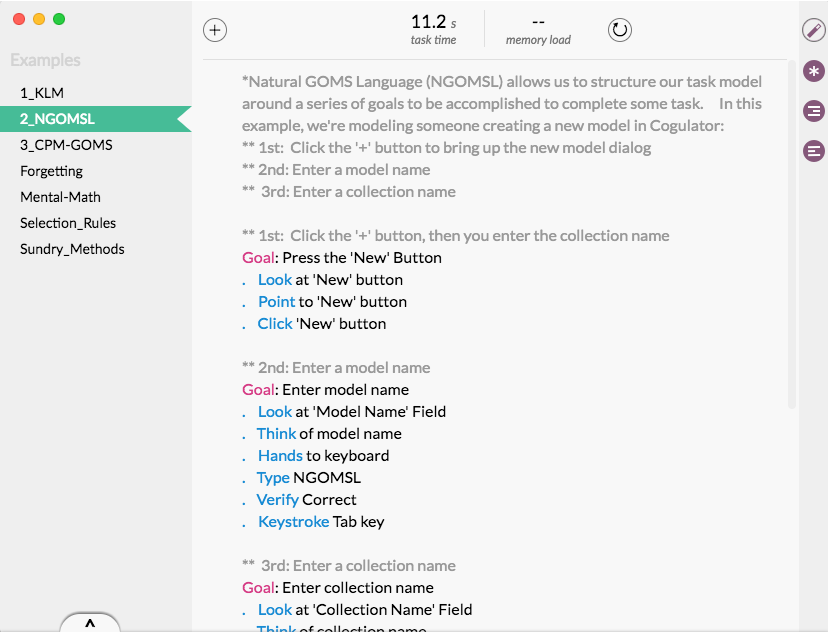

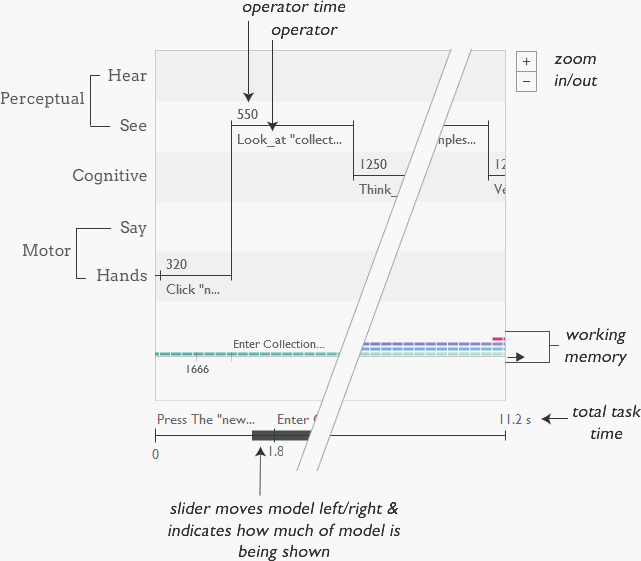

At its most basic, Cogulator is a GOMS text editor and, as such, the primary interface component is for text entry (see image below). In addition, there are interface elements for managing existing models, reviewing and inserting operators into a model, a Gantt chart visualization of the model, and a display that provides the estimated task time, working memory load, and workoad estimate (if available).

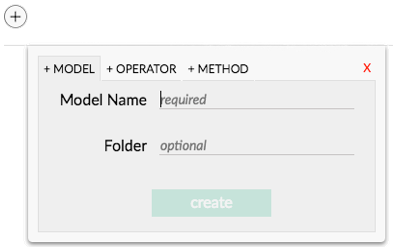

New Models

To build a new model, click the new model button. Doing so presents a dialogue box with two blank fields. Input into the collection field is optional. Collections allow you to place models into groups (discussed in more detail in the Management section). A model name is required. The name must be unique and contain no spaces (underscores will automatically be inserted in place of spaces as you type). If you try to enter a model name that already exists, a red “x” will appear next to the name field along with a note indicating the model name is already in use. Once a unique model name is entered into the text field, you can press the "create" button, which will create the new model.

Saving Models

In Cogulator, every time the application is closed or a new model is opened, the currently open model is saved automatically. You can manually save the model at any time by pressing the save button located to the right of the new model button.

Model Management

It's often nice to be able to quickly open other models to borrow commonly used methods. As such, Cogulator takes a slightly different approach to file management. Rather than the traditional File > Open process, all existing models are listed along the left side of the interface (a la Brackets) for easy access to other models. The currently open model is noted with a small arrow indicator. When you first install Cogulator, a default set of models will be included in the Examples collection.

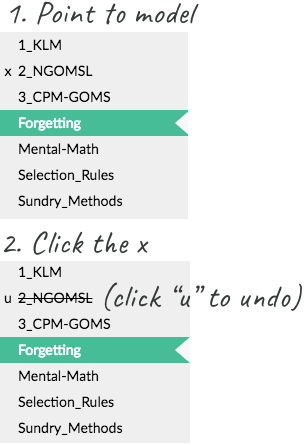

To open a model, find it in the list and click it. Models can be marked for deletion by hovering over the model name and then clicking the “x” that appears to the far left. At this point the model has not actually been deleted and you can undo this action by hovering over the name again and click the “u” button (located where the “x” was). Any models marked for deletion will be moved to the trash when the application is closed.

Magic Models

Most interface designers don't have any real experience with GOMS. Even if you have some experience, you might not be entirely confident on how string operators together to get a reasonable task model. The Magic Models feature is our first attempt to address this problem, making it possible to build a model in Cogulator without knowing an operator from a selection rule. With magic models, you demonstrate to Cogulator how a task is completed on a desktop/laptop computer or touchscreen device (e.g., iPhone). Cogulator then automatically generates the GOMS for you.

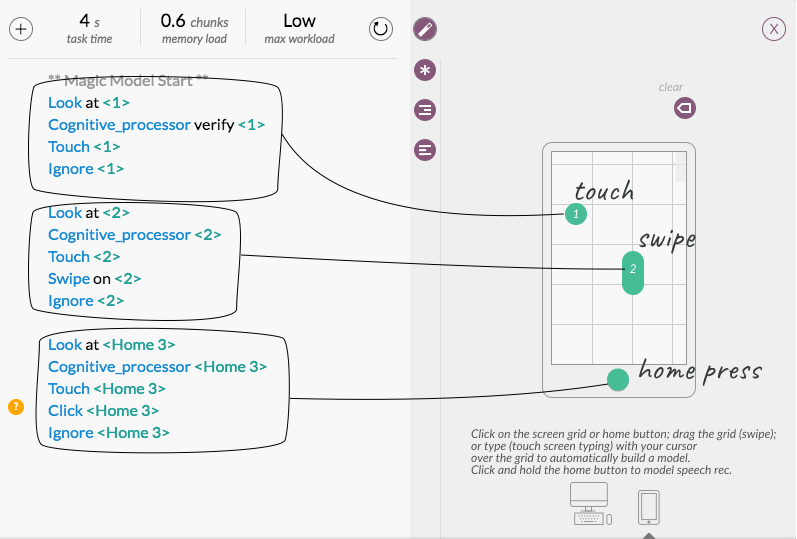

To get started with magic models, press the  in the menu near the top of the interface. That'll bring up the magic models window. You can switch between desktop and touchscreen phone interfaces with the button at the bottom of the window. In the desktop, you can click on the grid to demonstrate point and click, drag the bar on the right side to demonstrate scrolling, or type to demonstrate, well, typing. Each mouse action is marked and labeled on the grid. You'll see the automatically generate code in the preview window next to the desktop.

in the menu near the top of the interface. That'll bring up the magic models window. You can switch between desktop and touchscreen phone interfaces with the button at the bottom of the window. In the desktop, you can click on the grid to demonstrate point and click, drag the bar on the right side to demonstrate scrolling, or type to demonstrate, well, typing. Each mouse action is marked and labeled on the grid. You'll see the automatically generate code in the preview window next to the desktop.

With the touchscreen phone option, you can demonstrate touching the screen, tapping a series of things on the screen (as when typing using the touch keyboard), swiping up or down (click the grid and drag it for swipe), pressing the home button, and speech rec. For speech rec, press and hold the home button. After about a second, a blue window will pop up and guide you through demonstrating the rest of the action. That will include typing in the speech rec command as well as any response from the phone (e.g., "Call John". "OK, dialing John").

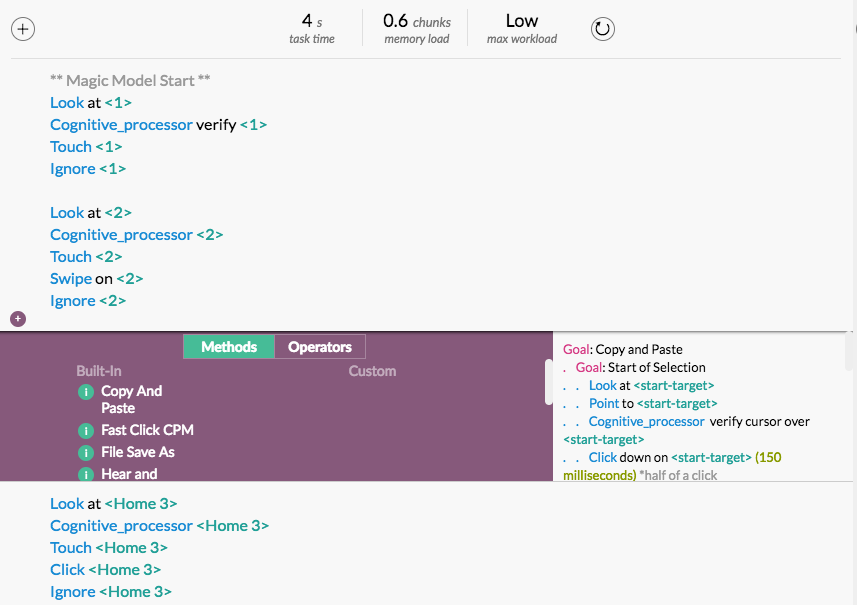

Operators & Methods

Even those familiar with GOMS may have a difficult time remembering all the operators available and their specific formatting requirements. In order to help, we’ve provided an Operators and Methods insertion tool. Influenced by Bret Victor’s “dump the parts bucket on the floor” strategy, the insert tool lists all available operators and methods. To access it, click on any blank line in the model. To the left of that line a  will appear. Click on that, will bring up the insert tool. Clicking on an operator or method in the list will insert it at the selected line. For information about the operator or method, press the

will appear. Click on that, will bring up the insert tool. Clicking on an operator or method in the list will insert it at the selected line. For information about the operator or method, press the  next to the operator/method.

next to the operator/method.

Errors & Tips Interface

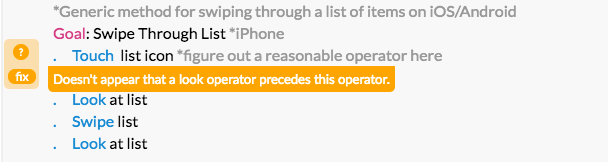

Inevitably you’ll make some errors as you begin working with the CMN-GOMS syntax. Cogulator has some initial, rudimentary error color-coding in place to help you along the way. When an error is detected, a  is placed on the error line. Hover over the

is placed on the error line. Hover over the  to display a description of the error.

to display a description of the error.

In addition to error indicators, Cogulator suggests tips for improving the model. For example, modelers often forget to use a Hands operator when the user moves their hands from the mouse to the keyboard (or vice versa). When a tip is available,  is displayed next to the line. In some cases, Cogulator can implement the tip for you. When that option is available, a fix button will be displayed when you hover over the

is displayed next to the line. In some cases, Cogulator can implement the tip for you. When that option is available, a fix button will be displayed when you hover over the  . Clicking the fix button will implement the tip.

. Clicking the fix button will implement the tip.

Gantt Chart

At the bottom of the interface is an up arrow which brings up the Gantt chart. The Gantt chart visualizes the model, showing each operator time, what resources it uses, and instances of parallel execution (discussed in the next section). Note that clicking on an operator in the Gantt chart will take you the corresponding line in the model syntax. Clicking the camera icon located at the bottom left of the chart will save a screenshot of the chart to your desktop.

Multitasking

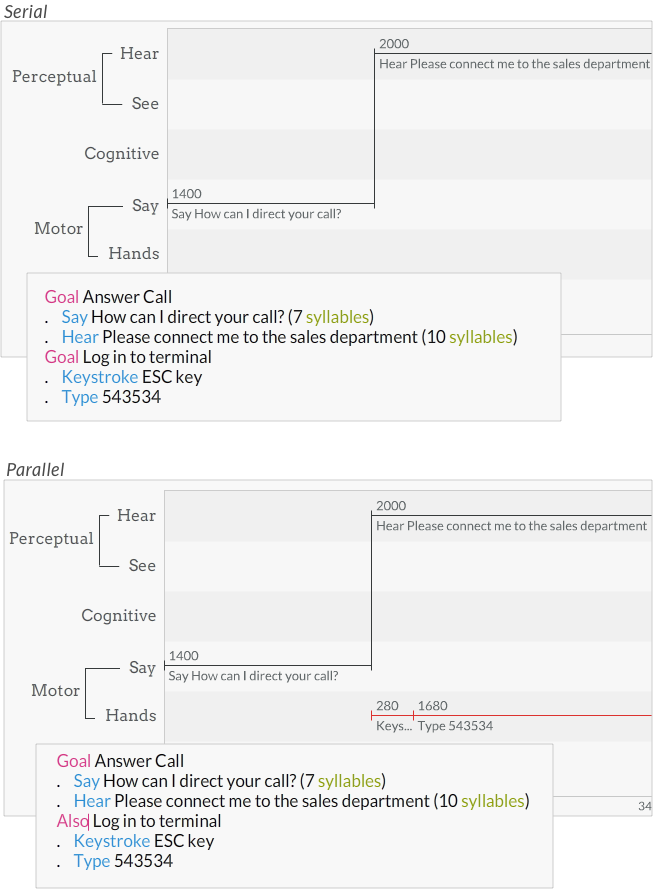

Borrowing from NGOMSL, Cogulator allows for multitasking via the Also statement. So, should a goal need to be executed in a parallel with another goal:

. Goal: Point and Click

would be replaced with

. Also: Point and Click

Adding "as hands" to the end of the "Also:" line would ensure that multiple methods are on this same thread. You can think of a thread as adding a new lane to a highway. Everything that has the same label after the "as" will be in the same lane and therefore will happen serially. Operators in other threads can occur in parallel to the new thread. As with operator labels, the thread label is user-defined.

Parallel execution is visualized in the Gantt chart. An example of parallel and serial execution of the same tasks is depicted in the image below. In the example, an imagined telephone operator needs to log into a workstation just as they receive their first call. In the serial example (upper panel), the call is received and then the operator logs in. These tasks happen in parallel in the lower panel. Note that new threads are randomly assigned their own color (orange in this example) to distinguish them from the base thread.

Working Memory Load

Working Memory load is a important driver of Mental Workload. To model working memory in Cogulator, we used chunk naming. Each chunk added to working memory is represented as a colored block in the Gantt chart. Over time, those memories begin to decay, until they're no longer accessible. That decay is symbolized in the chart with the use of transparency - the blocks becoming more and more translucent until they leave memory altogether. The primacy and recency effects of memory are accounted for in the current algorithm.

To name a chunk, simply place angled brackets around it like so…

. Look at <fred@cog.com>

This places one chunk (fred@cog.com) in memory. Suppose that you are unfamiliar with both the recipient and the domain. In the case, you could choose to place two chunks in memory…

. Look at <fred> <@cog.com>

To add a named chunk to working memory, it needs to be used in conjunction with one of the operators we mentioned earlier (Recall, Look, Search, Perceptual_processor, Hear, or Think). If the named chunk is in working memory and you pair it with one of these operators again, it’ll add activation to the existing chunk. Using a named chunk without one of these operators will let Cogulator know you want to test whether it is still in memory. That is, whether it’s been forgotten.

Take a look at the following model…

. Look at <fred@cog.com>

. Think what to say (60 seconds)

. Type <fred@cog.com>

Notice that in the Type step, “fred@cog.com” is red. The email address was added to working memory with the "Look", but the red highlighting indicates that it took so long to think of what you wanted to write, the email address was forgotten. In the model, this is easily resolved by looking at the email address again right before typing your message.

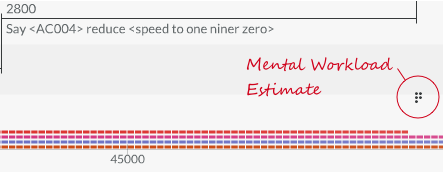

Mental Workload

Chunk naming also enables estimates of subjective mental workload. Any time a named chunk is referenced in a step that does not use one of the automated working memory operators (Recall, Look, Search, Perceptual_processor, Listen, or Think), we show a mental workload estimate on the chart. This is an estimate of how the user might rate their mental workload on a scale of 1 to 10. The number of dots corresponds to the workload rating. We can see a rating of 5 in the chart below. That estimate is based on the activation of the chunk "speed to one niner zero"

These estimates are based on some work on a series of simple experiments I conducted (see the Workload Curve). Keep in mind, though based in research, both forgetting and mental workload estimates are experimental features.

@References

It's fairly common to use a method like Point and Click repeatedly in a model. For example...

Goal: Point Click

. Look at target

. Point to target

. Verify cursor over target

And, when you want to use a basic method repeatedly, it's a pain to have to retype it each time. So, we've added something to Cogulator we call a reference. With a reference, you can tell Cogulator to repeat an already declared method later in the model by simply entering the Goal name with "@", like so...

@Goal: Point Click

This tells Cogulator to repeat the earlier method. If you have chunk names in your method, you can add those to both the intial Goal declearation, and the reference like so...

Goal: Point Click <target>

. Look at <target>

. Point to <target>

. Verify cursor over <target>

@Goal: Point Click <button>

In the example above, adding "<target>" to the goal statement, and "<button>" to the @goal reference results in Cogulator using the named chunk "button" the second time the method is executed rather than "target".

Selection Rules

Selection Rules are If/Then statements commonly used in GOMS. Many people won't ever need selection rules, but for those who do, it's a handy feature (developed by NC State students Prairie Rose Goodwin and Nischal Shrestha). To use selection rules, you'll need:

CreateState

SetState

If

EndIf

Goto

You'll start with CreateState, which allows you to name an object and give that object a state. For example:

CreateState theLights areOff

In this case, my object is "theLights" and the state I've assigned is "areOff". The object and state can be anything you want them to be, so long as each are one word without spaces.

Once I have a state, I can use it in a selection rule like so:

CreateState theLights areOff

If theLights areOff

. Hands to the light switch

. Turn the light switch on

EndIf

Basically, if the lights are off, then do everything between the If and EndIf. Once I've modeled the user turning the lights on, I likely want to set the state to reflect that, which I can do with SetState:

CreateState theLights areOff

If theLights areOff

. Hands to the light switch

. Turn the light switch on

. SetState theLights areOn

EndIf

We also have a Goto option. Goto does just what you think it would: it tells Cogulator to skip directly to a specific goal in the model. Here's an example:

CreateState theLights areOn

If theLights areOn

. Goto Goal Greeting

EndIf

Goal Turn the Lights On

. Hands to the light switch

. Turn the light switch on

. SetState theLights areOn

Goal Greeting

. Say I see you

In this model, we start by testing to see if "theLights" "areOn". Because they are, we jump directly to the goal Greeting (i.e., Goto Goal Greeting).

A Reprieve

That covers Cogulator at a high level. If this all seems a bit complex, remember that you can model at a lot of different levels of fidelity in Cogulator. Starting with some of the simpler modeling methods like KLM is a great way to get comfortable with GOMS and Cogulator. Take advantage of the example models that come installed with Cogulator. You may also find the primer video helpful. It's brief and just covers the basics.